mRNA Vaccines: Questions & Misconceptions

There are a lot of questions and misconceptions about mRNA vaccines (especially for SARS-CoV-2 or COVID19). In this video, I'm answering 10 of the most frequently asked questions from my viewers.

I'm not trying to convince you of anything. Feel free to check out my sources and do your own research.

Overview of questions:

- Q1: Is this video sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry?

- Q2: Why is a vaccine necessary?

- Q3: Will the vaccine prevent the virus from spreading?

- Q4: How is the efficacy of a vaccine determined? (The 95%)

- Q5: mRNA vaccines have never been approved before. They are unsafe and rushed.

- Q6: Why can't we use traditional vaccines?

- Q7: Can the mRNA in the vaccine alter my DNA?

- Q8: What are the adjuvants? And are those dangerous?

- Q9: Why do some people get sick from the vaccine?

- Q10: The coronavirus is mutating. Will the vaccine protect me from those mutations?

Q1: Is this video sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry?

No, it wasn't sponsored by anyone. In fact, so far, none of the Simply Explained videos have been sponsored. This one is no exception. If you want to help and keep this channel independent, consider becoming a member.

No, it wasn't sponsored by anyone. In fact, so far, none of the Simply Explained videos have been sponsored. This one is no exception. If you want to help and keep this channel independent, consider becoming a member.

Source: myself.

Q2: Why is a vaccine necessary?

As this viewer points out, our immune system is quite capable. A vaccine is merely a helping hand, strengthening our immune system so that fewer people need to be hospitalized and fewer people die.

As this viewer points out, our immune system is quite capable. A vaccine is merely a helping hand, strengthening our immune system so that fewer people need to be hospitalized and fewer people die.

According to John Hopkins University, COVID19 has an observed case-fatality rate between 0,5% and 10%.

Let's take 2% as the average and assume that everyone on Earth got infected (7,7 billion people). We would be looking at 154 million deaths.

We can largely prevent these huge losses by developing vaccines. So it makes a lot of sense to immunize as many people as we can.

Note: The fatality ratio isn't 100% accurate because some infections aren't detected and some people could die of COVID19 without knowing.

Sources:

Q3: Will the vaccine prevent the virus from spreading?

That's not clear at the moment. After vaccination, your body will start making a specific type of antibody that will circulate in your bloodstream.

However, the coronavirus enters our body mostly through our nose, and here we have different types of antibodies. It's currently not known how effective the vaccine's antibodies will be in this region. That means you won't get sick, but you could still have virus particles in your nose, ready to spread to others.

That's also why vaccinated people can still test positive for the virus while not getting sick.

But there is hope. One study exposed vaccinated primates to the virus and observed that they were able to clear the infection from their airways in a shorter time than others. Indicating the vaccine reduced how long they were infectious.

Time will tell if the same holds up for humans.

Sources:

Q4: How is the efficacy of a vaccine determined? (The 95%)

The efficacy expresses the reduction of infections between vaccinated people and unvaccinated people.

Let's take a real phase 3 study as an example. In this case, there were 36,523 participants, half of which got the vaccine, the other half got a placebo. Participants were closely monitored for 120 days while keeping track of COVID19 infections.

In the group that received the vaccine, 8 people eventually got COVID19. In the placebo group, there were a total of 162 cases.

The efficacy is then calculated by taking the difference between these groups and dividing them by the number of cases in the unvaccinated group. This gives us a 95% efficacy.

With:

- VE = Vaccine efficacy

- ARU = Attack rate unvaccinated people

- ARV = Attack rate vaccinated people

This approach has been used many times before and is not new.

Sources:

Q5: mRNA vaccines have never been approved before. They are unsafe and rushed.

This is indeed the first time that mRNA vaccines are approved. But that's not because they were rushed or corners were cut.

First up: mRNA technology isn't new. It's been researched and worked for more than 2 decades. It's only now that the technology has matured enough for wide-spread use.

Secondly, we already studied other coronaviruses, such as SARS, in great detail. These have similar spikes, so we could build upon this knowledge.

Thirdly, there was a lot of money available for research and production. The US alone invested over 10 billion dollars into developing vaccines (Operation Warp Speed). This meant that companies could conduct clinical trials in parallel while also ramping up manufacturing. Here's how vaccines are traditionally developed, notice how it's very sequential, one step at a time. And this is how the COVID19 vaccines were developed. You can see that many steps were conducted in parallel, massively speeding up the process. Not skipping steps, but doing them at the same time.

And finally, regulatory agencies such as the FDA and EMA gave priority to all studies related to COVID19. Companies were allowed to periodically submit parts of their research for approval. This shortens the review times.

So, in summary: The vaccines were not rushed. They've been massively accelerated.

Sources:

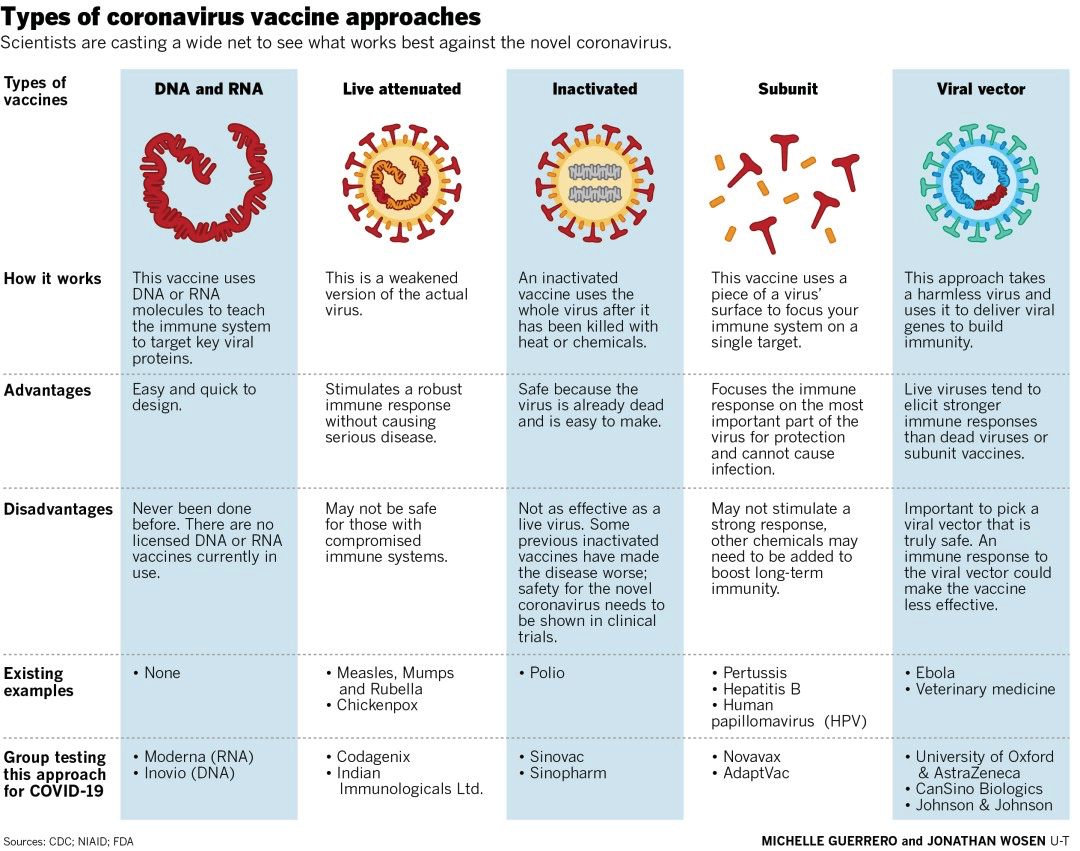

Q6: Why can't we use traditional vaccines?

We can, and we do. There are many types of vaccines, and mRNA is just one of them. An older and more commonly used technique is to use weakened viruses to boost your immune system.

I won't go too much into details since this video focuses primarily on mRNA. But here's a handy overview of the types of vaccines and which company is working on them for COVID19.

Source: The San Diego Union-Tribune

Source: The San Diego Union-Tribune

Sources:

Q7: Can the mRNA in the vaccine alter my DNA?

No. Our DNA is contained in the nucleus of our cells. While mRNA does enter our cells, it cannot enter the cell nucleus.

mRNA is naturally made by our body. When a cell needs a particular protein, the cell nucleus will make a string of mRNA containing instructions and give it to the rest of the cell for execution. So all we're doing with the vaccine, is temporarily give our cells other instructions.

Side fact: viruses that do "become a part of us" are called retroviruses. The most commonly known one is HIV.

Sources

Q8: What are the adjuvants? And are those dangerous?

No, they aren't dangerous. Adjuvants are used in almost all vaccines for the last 70 years. They signal your immune system to come to check out what is happing near the place where you got injected with the vaccine.

That way, the immune system will more quickly notice the odd spikes in your body, resulting in a more robust immune response with more antibodies.

Q9: Why do some people get sick from the vaccine?

It's not uncommon for vaccines to have some side-effects, and the ones for the coronavirus are no different. In this phase 3 study, side-effects were common but mild. This included pain at the injection site, fever, tiredness, chills, and headaches.

It also found that participants had more side-effects from the second dose than the first dose and that people older than 55 reported fewer side-effects than younger participants.

In summary: the mRNA vaccines are generally well tolerated. In most cases, having some mild side-effects is better than actually having to fight off COVID19.

Sources:

Q10: The coronavirus is mutating. Will the vaccine protect me from those mutations?

We're talking about the UK and South-Africa mutations, which allow the virus to spread more rapidly.

Early studies indicate that the mRNA vaccines might be just as effective against the UK mutation. In this study, researchers took antibodies from people that had received the 2 doses of their vaccine and exposed them to the mutation. They found no reduction in neutralization activity. In other words: the mutated virus did not develop a resistance against the antibodies produced by the vaccine shot.

The South-African mutation is a different story. That same study found a significant reduction in neutralization activity, but they noted that the vaccine would still be effective. Some companies are already working on tweaked versions of their vaccines to offer full protection.

However, we do have to be cautious with this data. It's an early study so nothing conclusive just yet.